Local Hiking Ketchikan

- Home

- Explore Ketchikan Alaska

- Local Trails

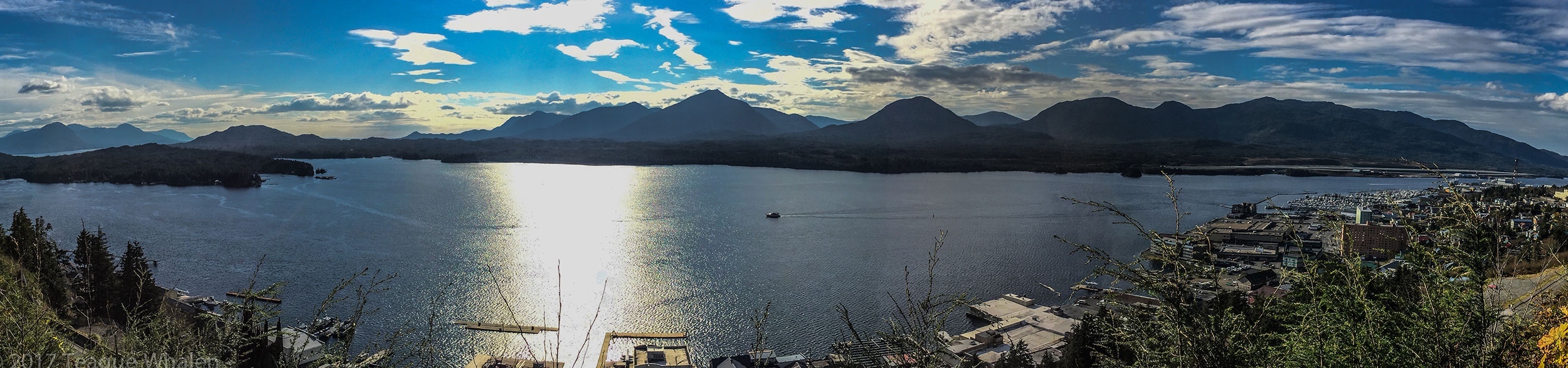

Hello From Out The Road

Hello, I’m Teague Whalen, a local resident of Ketchikan, Alaska, and I am here to guide you through your trail research during your stay in Ketchikan. I’ve assembled a couple handfuls of trail write-ups for your reading pleasure that synthesize personal stories from my trail experiences with some practical information about what to expect on each of these trails. If you are an experienced hiker, feel free to skip ahead, read what our trails have to offer, and choose your next adventure. However, if you are a less experienced hiker, or this is your first time to Southeast Alaska, or you are someone who likes to learn as much as you can about a place before you get there, this introduction to hiking in Ketchikan will sketch in what to expect for weather, suggested gear to bring, what not to worry about concerning bears, and some safety tips concerning hiking in Southeast Alaska.

Read MoreEnsuring that you have a successful adventure starts with being smart about your planning, and I can tell that you already are because here you are doing your research in order to get a glimpse of what you may be getting yourself into. However, I hope to leave some magical mystery for you to discover about each trail’s charm on your own, given enough to get started and to help you choose wisely which path may be next for you. If there is one thing I know about, it’s hiking and how to do it safely in Southeast Alaska. I’ve started a summer hiking tour here in Ketchikan: Mindfulness Rainforest Treks, LLC, which is a guided hike on the Coast Guard Beach trail. I am passionate about healthy living and connecting to nature and people and have found hiking Ketchikan’s trails to be a wonderful way to accomplish these things. To learn more about me, please click here: A Little About Your Trail Guru.

If anyone would like to supplement the information provided in this hiking website with a copy of the National Forest Service’s Ketchikan Area Trails Guide, photocopies can be picked up at The Alaska Fish House or online at the National Forest Service website Ketchikan Area Trails Guide. Before you read on, please understand that I and/or the owners of Explore Ketchikan website are not liable for any of the subjective information presented in this introduction and in each of the trail vignettes. Each person who ventures out on any of the trails in and around Ketchikan does so at their own risk and will be responsible for his/her own safety, choices, consequences, and of course enjoyment. To learn more about how to be safe, click here: Top Ten Ways To Avoid A Bad Ending. Now that we’ve got that out the way . . .

In The Land of Ferries, Float Planes, & Mountain Goats

I’ve never lived so close to such amazing backcountry hiking. As we really only have one forty-mile road that stretches along the edge of Revillagigedo Island, all the trails on our road system are usually just minutes away. As soon as you step foot on the trails here, you are walking into a dense rainforest canopy of Sitka spruce, western red cedar, hemlock, and alders, and a trail brushed with devil’s club, skunk cabbage, ferns, and a plethora of berry bushes—salmonberries, blueberries, huckleberries, and thimbleberries to name a few. Many species of mushroom and moss grow abundantly here as well. As you hike into the higher elevations on the mountain trails, you may find yourself walking through much more open muskeg meadows, with thinner and smaller mountain hemlock, yellow cedar, and the tough, knee-sized krummholz. In order to help better identify the flora here in Southeast Alaska, I highly recommend Jim Pojar’s and Andy MacKinnon’s Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast. You may also want to pick up books on edible berries and mushrooms as well. A good place for information, brochures, and maps is our Discovery Center, run by the U.S. Forest Service, just a block over from the cruise ship berths and right next door to the Alaska Fish House. The U.S. Forest Service’s website offers information here on Alaskan poisonous plants and information on mushrooms here: Mushrooms of the National Forests of Alaska. A good rule of thumb is: if you don’t know what it is for sure, don’t eat it.

As soon as you are walking away from town, nothing but wilderness stretches ahead of you for hundreds of miles. Much of the wilderness is very difficult to access; often the only ways to get into the backcountry is by foot, boat, float plane, or any combination of these. Hiking off trail is very difficult here and not at all recommended for newcomers solo hiking. When leaving the trail, people do get lost in these woods and sometimes do not return. But most of the trails we do have are well-marked and easy to follow. The difficulty can be if the trails are covered in snow, then it’s not so easy. Our mountains hover around 3000-feet tall and often with a base starting right at or near sea-level, so that’s an entire 3000 feet of vertical from base to peak. Some of the higher elevations, such as hiking up toward Minerva Mountain from Carlanna Lake, you have to keep an eye out for the cairns to direct your path because there are not tall trees upon which to place markers, only a steep, vegetation-spotted rock slope. Even though our mountains are on the small side, we still have tree-lines on some of the mountains because of our northern latitude and extreme climate. Once you are in the alpine country, you may be above the tree-line and will only have the path below your feet to follow. Often, the direction to go can be pretty clear once you are up on the mountain ridges and tops because there are very limited choices of where to go due to precipice drop-offs. Usually during clear sunny days, visually orienting one’s self can be easier if you are familiar with the landmarks, such as other mountains, the ocean, and where north, west, east, and south are. However, if the high country is socked in with clouds, rain, or snow, navigating can become extremely difficult and sometimes dangerous, so a GPS and map are highly recommended to have along in case of such an event.

For more challenging hiking, we have two mountain traverses here. The Deer Mountain to Silvis Lakes traverse is a fourteen-mile, one-way trek across some remote alpine country and climbs over Deer Mountain and Northbird Peak, skirts just below John Mountain and Mahoney Mountain, and ends up at the south end of the Tongass Highway. The Carlanna Lake to Perseverance Lake traverse is roughly ten miles, one way, and climbs over Juno and Ward Mountains. These traverses can be done in a day or broken up if one is willing to bring camping equipment along. People should only attempt these traverses if they are in great shape, are very good at sniffing out a faint alpine trail, know how to read the weather, and are proficient with using topographical maps with a compass or GPS. Several people have gotten into trouble on these traverses, especially the more popular Deer Mountain to Silvis Lake traverse. Do not underestimate the rigors of a traverse that crosses multiple mountains.

Cell-phone coverage can be very spotty on many of these trails. Without getting into each trail specifically, here’s a good way of thinking about how cell reception may work here. Out north and out south at the end of the Tongass Highway, there generally isn’t any cell service, nor for the trails there. Trails that can be accessed right out of town are generally a safe bet for cell service, all the way up to the peaks as long as you are on the town-side of the mountains. The Ward Lake area trails generally have cell service, except for the further you go into the backcountry out Revilla Road or out one of the longer trails like Perseverance Lake or Connell Lake. This area happens to be on the other side of the mountain ridges from town. Reaching ridges and summits again makes for a better chance of connecting with cell-phone towers from town. If you are in a cell-phone dead zone, it is often helpful to power down your phone so that the device doesn’t quickly drain from trying to continually search for service, thus preserving power for when you may need to use your phone for photos, time-checks, or emergencies. Otherwise, remember that you really aren’t out here to stare at your phone and check emails or Facebook because once you do, the Alaskan wilderness is already lost on you.

Transportation to the trails can be one of a few different options. If you already live in Alaska, you may consider putting your car on a state ferry so that you have your own vehicle for exploring the Ketchikan area. For those of you who are arriving by plane or boat, we have a rental car service that is offered both at the Ketchikan International Airport, which is on Gravina Island, and also here on Tongass Highway roughly two miles north from downtown. At this time, Ketchikan does not offer an Uber service, but we do have taxicabs whose drivers are willing to drive and pick you up from anywhere you’d like to go. We also have public bus transportation that goes out north as far as North Point Higgins Road, which is roughly near the fourteen-mile marker and goes out south as far as Franklin Roosevelt Road, about 6.5 miles. For any hiking off the road system, several float-plane businesses are available for hire as well as Baranof Excursions, a popular local charter fishing company with boats that can transport people to remote cabins and trails in the surrounding area. Of course, sometimes aviation and marine transportation can be canceled due to unnavigable weather.

Close

Coast Guard Beach

- 2 miles round-trip (1-2 hours)

- 170 feet elevation loss to sea-level

From downtown Ketchikan, 14 miles north on Tongass Hwy. Turn left onto North Point Higgins Road. Take 1 mile until the road swings a hard left and then dead-ends at the North Point Higgins Elementary School parking lot. Trailhead is located at the far end of the parking lot, closest to the playground.

Wherever I’ve lived, I’ve had a Sunday late-afternoon or early-evening walk that has helped me to work out those upcoming Monday returning-to-work blues. Sunday evenings growing up, my father and I, and sometimes my younger sisters and my mother (and a dog), would often hike at our closest wooded state park in Southeast Michigan—Highland Recreation Area. It was a time for us to talk about anything we wanted or to walk together in quiet peace. The place that has become that spot for me, and much more, in the Ketchikan area, is the Coast Guard Beach trail.

The trail is roughly equidistant from my house and my girlfriend’s house, which makes it a convenient rendezvous point for us. Our first weekend spent together found us hiking down this trail to enjoy time on the beach. When the sun is out, this beach just can’t be beat. The beach is literally nearly in my backyard, as the south end of the beach begins at the north end of my neighborhood, and sometimes I walk to the beach from my house. But often I prefer making the quick drive to the elementary school in order to access the beautiful trail that takes me to the north end of the beach.

The gravel trail was built by a local group of volunteers and winds through Ketchikan Gateway Borough land and then crosses into Alaska Mental Health Trust Land. The first stretch of trail walks along the edge of a large muskeg flat overlooking a background of mountains when you can see them over the treetops. Here, silvered and charred pines stand naked due to a 4th of July fireworks mishap one very dry summer. This muskeg reminds me of the flat, jack-pine-riddled wetlands of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula where I used to live, a place that sees its fair share of forest fires. After the muskeg, the trail bears right and begins stepping down into the rain forest, where huckleberries and blueberries can be found in season. Mostly the trail descends to the beach; however, a few hills do rise along the way. Some large western red cedars can be seen beside the trail. One had fallen across the trail just before my girlfriend and I ventured down during our first weekend together. The large trunk can’t be missed now as it berms the north side of the trail. Here you can begin to see glimpses of the how close you are to the ocean through the thinning branches. Just around the corner is a steep, rocky descent to a smaller stone-cobbled beach on the right. I recommend only sure-footed hikers or those who are confident in their use of trekking poles to navigate this unmaintained part of the trail. Depending on the tide, this can be a very nice beach for some limited privacy, that is until the next hikers decide to join you or the next fishing boat floats by. At this beach, you get a nice view of the Cleveland Peninsula, which is the main land jutting into the Tongass Narrows, and a limited view of Prince of Wales Island across the way. Once when taking a group of friends down this trail, one friend’s rock-chewing dog was in heaven on this beach and couldn’t get enough of chomping on cantaloupe-sized rocks and prancing around with each one.

Moving on from here, soon a longer hill rises with some steep slopes falling off the side of the trail, so watch your footing. On the backside of this hill are some shorter but steep descents that may be best navigated with a trekking pole for those who are not sure-footed or very balanced. Once while hiking along quietly here, I heard a whale exhale out her blow spout; she was that close! Soon you will cross a wooden bridge over a small creek, where you should be able to see and hear the ocean meeting the wave-polished stone beach. The trail will dump you right between two outcroppings of jagged rocks, where if the tide is low, you can walk on out onto the beach, which opens up wide to the left. If the tide is higher, I like to sit on one of these outcroppings and just watch the ocean, sky, and the distant mountains of Prince of Wales and Cleveland Peninsula. Once while sitting here, a rookery of seals dove beneath the surface and swam toward me, pushing the herring toward shore where the seals could trap and eat them right in front of where I was perched. Then they’d swim back out from shore, regroup, and do it again. I watched them do this for about forty-five minutes until they moved on.

If the tide is high and you want to access the rest of the beach, you will need to cut through the forest on the left and hop across a creek, where there’s a half buried, rusted out, army-truck chassis. It seems without fail, many different waterfowl can be seen coming through or floating out on the ocean here. Besides seals, sea lions sometimes make an appearance, and occasionally orcas and humpback whales. One sunny fall afternoon, my girlfriend and I watched humpbacks’ blow spouts occur in multiple directions. Only accessible by boat or foot, this rocky pine shore reminds me quite a lot of Canada’s north shore of Lake Superior, my old stomping grounds. And one of the things that I miss the most about the Great Lake State of Michigan, I can sometimes hear at Coast Guard Beach—the simple, rhythmic sound of waves crashing on the shore. Takes me right home. And because of this, this beach is one of my favorite places to do tai chi for about forty minutes.

This beach is a good place for walking, sunbathing, beachcombing, photography, writing, meditation, tai-chi, just sitting, marine-life viewing, and dog swimming. And often in the summertime, all of a sudden a cruise ship floats out of the woods on the south-end of the beach and fills your view on its way to points north. Another time, my girlfriend and I saw a cruise ship heading toward the Behm Canal that goes around our island, Revillagigedo, instead of heading north towards Wrangell and Juneau. I said, “Something’s not right. Are they lost?” And then the ship turned around and was heading for Prince of Wales, still the wrong direction. Next it was heading back our direction. We watched this silly back and forth a bit and then hiked out. The next day my girlfriend heard that the ship’s steering had broken and they had limped back into Ketchikan and waited until someone could fix what was broken.

On a quieter day, I saw two men further down the beach, standing bare chested and waste deep in the ocean, their forearms reaching out as they faced the north and chanted in a language I didn’t understand. They looked cold, but tough and determined. After they slowly backed out of the ocean, they built a small fire, dried off, and dressed. My girlfriend knew that I really wanted to go over and talk with them in order to find out what spiritual activity they may have been engaged in. But I respected whatever their ritual was and gave them their space. They did make me think of something that I had read by the late Alaskan marine biologist and writer, Eva Saulitis, who states in her book Leaving Resurrection: Chronicles of a Whale Scientist: “According to traditional stories of Old Chenega, humans turn into killer whales when they die. When killer whales come close to a village, the people believe they are calling someone” (183). While attending the Association of Writers and Writing Programs’ annual conference in Seattle in the spring of 2014, I had the luxury of seeing Ms. Saulitis share the stage in Seattle with former Alaska Writer Laureate, Peggy Shumaker, and former Pulitzer-Prize winning poets, Robert Haas and Gary Snyder. Sadly, in January of 2016, Eva died from breast cancer, but I take heart that she has returned to the ocean in the form she may have loved most, that of a killer whale, the very thing she dedicated much of her life to studying. And with a little patience and luck, you might just be graced with a pod of orcas that sometimes passes through these waters just off of Coast Guard Beach, on their way to who knows whose village they may visit next as bits of poetry trail behind in their wake.

Connell Lake

- 4 miles round-trip (3 hours)

- 100 feet elevation gain

From downtown Ketchikan, 6 miles north on Tongass Hwy to Ward Cove. Right on Revilla Rd. for just over 2 miles. Just past Last Chance Campground, turn right on Connell Lake Rd. and take this dirt road until it ends at the parking lot on Connell Lake. The trailhead begins at the far end of the parking lot.

Also within the Tongass National Forest, Connell Lake is dammed where Ward Creek drains out at the southwest end, right beside the parking lot where the road comes in. From the trailhead, the rocky, dirt path gently climbs through the rainforest canopy and hugs the shoreline of the lake for most of the trail. Soon you’ll come across a small landslide that the trail bumps over and through. Then you dip down some log steps and climb a little again. Soon you’ll come to a boardwalk, which will bring you to a bridge over a large creek. On the other side is a nice flat area that the creek bows around, creating a small peninsula. A fire-pit indicates that this is a preferred spot to spend some time or camp.

Every time I come to this bridge to the peninsula, I smile and remember the time that I walked to this spot with my sister and her dog, which is an American Bulldog and Pitbull mix. She threw a stick into the river for him to fetch, but it sank. To our surprise, the dog dove under and retrieved it. This was when we found out that he had webbed feet and must also have some sort of retriever in his blood too.

We thought it was so funny that he kept diving in after the sinking stick each time she threw it.

From here, the trail steps up and begins to curve around toward the northeastern end of the lake. After some ups and downs, you find yourself stepping down a steep set of steps to a boardwalk that crosses over a swampy graveyard of stumps in the lake and a panorama of the mountains that box Connell Lake in. This was always one of my favorite spots to rest and take in the scenery when I would run the trail. The trail again climbs up and swings left through the woods, crosses over a bridge and continues on for a while. You know you are getting closer to the end of the trail when the boardwalk begins again and walks you through some narrow and watery muskeg fields, leading you away from Connell Lake to finally walk alongside the creek that drains out of Talbot Lake. Soon, you will come across a strange bridge that crosses over the creek just before Talbot Lake, but the trail does not continue on here. Most likely this bridge is used for fisherman and hunters who want to gain this side of the creek and lakes.

Just a hop, skip, and a jump from here, the trail ends at a tent platform at the southwestern end of Talbot Lake, another serene and quiet getaway. During one of my runs, I met two women talking here at the end of the trail. Through a little conversation, I learned that they had hiked in together and that the younger woman used to date the older woman’s son. I thought it was great that these two women still maintained a relationship. Later on, I met the younger woman again when she taught a yoga class that I began taking, which is one of the reasons why I enjoy meeting people on trails; they often are kindred spirits.

Deer Mountain

- 5.5 miles roundtrip (5-8 hours)

- Elevation Gain: 2,600 feet

From downtown Ketchikan, head south on Stedman St. and cross the bridge over Ketchikan Creek. In about a quarter of a mile, turn left on Deermount St. for about a quarter of a mile until it ends. Turn right on Ketchikan Lakes Road. At the top of the hill at the stop sign, go straight and then take a quick right into the gravel parking lot.

Deer Mountain, Ketchikan’s idyllic backdrop, holds a special place in my heart in that it was the first trail I ever hiked when I first came to visit my sister in Ketchikan in the late 90s. This trail is one of the most accessible trails from downtown Ketchikan, like where my sister lived at the end of Married Man’s Trail at the time. So the morning of New Year’s Day, I began walking up Fair Street along Ketchikan Creek and then up the steep pitch of Ketchikan Lakes Road that leads to the city dump. At the top of the winding hill there, I walked over to the trailhead where two neighborhood dogs—a golden retriever and a smaller mutt—joined me on my trek and stayed with me all the way up the mountain and right back to my sister’s apartment where I let them in and gave them water and food.

The path briefly threads between a couple of residential lots and soon turns to a rocky trail that quickly begins to ascend. Weary from circling the dump, ravens often caw and click to each other from their perches in the high branches of the dense Sitka spruce forest that the trail switchbacks through. The well-built trail is often stepped with logs buried into the rocky soil at points and a few wooden bridges with railings cross over small streams. The air breathes fresh and full of moisture here and white water tumbles over rock in the lower reaches of the mountain.

About a mile up the trail, a small rock outcrop and an opening in the trees creates what we refer to as the “first overlook,” which gazes upon the city edge of Revillagigedo Island and across the Tongass Narrows at Pennock Island, Gravina Island, and Annett Island. Out further lies the Dixon Entrance and the open Pacific Ocean, where the southern tip of Prince of Wales Island ends on the right and the Percy Islands dot the passage on the left—both places where I’ve fished for halibut. Moving on, the trail flattens out a little as it skirts around the edge of the mountain before it begins its winding journey up again. Not far along is what I refer to as the “one-and-a-half outlook,” which is a new clearing from a landslide that peeled off the mountain side a few year ago in heavy rains. Here one of my favorite trees can be found. About half way across the barren rock left behind where the trail cuts through is a sentinel Sitka spruce that stood its ground like an unforgiving pointed bow in stormy seas. The spruce’s battered trunk is torn and scraped and debarked by the onslaught of trees and soil that ripped away a couple hundred feet above it, and here the tree split the landslide into two braids down the rest of the mountainside, thereby saving a whole shallow ridge of younger spruces’ lives. I marvel at the symbolic strength and courage that spruce unassumingly stands for.

From here, the trail begins to wind up and around for the next mile as one begins to climb onto the shoulder of Deer Mountain, where the forest begins to open up more. Eventually, the trail leads you to the “second overlook,” where to the right one can see the face of the peak a little way off yet where the trail continues, and to the left, is a short jaunt to a scenic view that looks out over Ketchikan far below and the mountains stretching west and north with the Pacific. Back in the ‘30s, the Civilian Conservation Corps built this trail up Deer Mountain and then some enthusiasts decided to haul supplies up to this shoulder of the mountain in order to build a lodge for backcountry skiers, until it burned down in the early ‘40s. Some locals still hike this trail in the winter to snowboard or downhill ski, but the alpine area of Deer Mountain is not to be underestimated. A few years ago a man in his 30s, who grew up here in Ketchikan, died in an avalanche while snowboarding. On my first hike up the mountain with the two dogs on New Year’s Day, on my way back down, I ran into the city mayor and a high-school English teacher hiking up to go telemarking. I told them that when I got to the face, I lost the trail, and it seemed that a snowboarder had used the long edge of his snowboard like a giant pick axe to haul him straight up the frozen, snow-packed face. The teacher said when the face got that way, they had to cut steps into it, which made her nervous every time.

But generally, in the summer months and early fall, the Deer Mountain peak is free from snow and the trail easy to follow as it switchbacks up the face with an expansive view of Ketchikan Lake down below, catching the town’s water from the mountain’s snowmelt and rain runoff as well as the same from Dude and Diane Mountains on the other side of the valley. Following the path across the bottom of the face, one comes to a fork in the trail. Take the trail right and continue ascending through the switchbacks up the peak’s face until the trail skirts around the right of the top, through some low, scraggly pines, and then curves back around from the rear of the peak and dumps you on top for a splendid view from the northwest peaks and Pacific to the southeast mainland peaks all the way into British Columbia, Canada.

In mid-August every year, some hearty locals gather to race in the Deer Mountain Challenge, a nearly 3-mile run that begins at Tatsuda’s IGA parking lot at sea-level in town and finishes at the top of Deer Mountain, where Champaign is offered. Of course, one still needs to save some energy for the hike back down too. Something else you may not expect happens up here too. Sometime in January or February a group of people hike up into the deep snows of Deer Mountain on a clear day and are greeted by a helicopter dropping two crate loads of boxes. Eventually when the evening darkens, a massive fireworks display is launched from the summit or sometimes the saddle area for the whole town to enjoy. From that far away, the fireworks sometimes look like a fizzling candle atop a birthday cake. But again, just another thing that adds to Ketchikan’s unique charm.

Depending on how much time and energy you have to spend in the Deer Mountain alpine, plenty more of alpine hiking awaits. Returning back down the face to the fork in the trail, amble off to the right maybe a quarter of a mile, and you can find the Deer Mountain shelter, built and maintained by the Forest Service. About 2 miles further is Blue Lake, a high lake nestled in among the ridges, where another shelter used to squat until it blew over in a storm. One Sunday, my girlfriend and I hiked up Deer Mountain and to Blue Lake for the day, where we basked on the shore in the quiet beauty and sun and then hiked back to spend the night in the Deer Mountain shelter. The shelter is an A frame complete with a wooden table and benches, which can be slept on as well, and offers a loft upstairs for sleeping too. In one corner sits a stove for heating the shelter, but the Forest Service recommends bringing your own stove fuel. You also need to bring your own everything—food, sleeping bags, toilet paper, etc. An outhouse is tucked away just beyond the shelter and back toward the trail lie some small pools for gathering water, which can be treated for hydration and cooking purposes. Because this shelter is so close to town, it often is heavily used and mistreated. My girlfriend, who worked for the Forest Service at the time, packed out a whole garbage bag of trash and stuff left behind.

Once we cleaned up the place and gave it a good sweeping, we walked down the trail a little and watched the sun set, Ketchikan’s hustle and bustle freeze-framed far below where we left our work and bills, where tomorrow we’d get up early with the sunrise and find Ketchikan and the whole narrows choked with impenetrable clouds, only us and the mountain peaks still enjoying the sun and blue sky above until we descended into the usual rain below in order to make it to work on time. But until our departure that next Monday morning, it seemed like we were the only ones on the planet, and the peace of the mountain stillness descended with the chill of night. The sky deepened and darkened. The stars began to pop out. Hand-in-hand, she and I walked back to our private mountain home that night, pleasantly worn out from the day’s excursions, our thoughts quiet, our companionship warm.

Dude Mountain

- 3 miles round-trip (2-4 hours+)

- 1500 feet elevation gain

From downtown Ketchikan, 6 miles north on Tongass Hwy to Ward Cove. Right on Revilla Rd. for 6 miles. Right on Brown Mountain Rd. for 3 miles until dead-ends at trailhead. Approximately forty-minutes.

Dude Mountain is one of my favorite hikes in Ketchikan and has actually become a traditional new-year hike for me. Now, my new-year is not the usual January 1st New Year’s Day. For much of my adult life, as an undergraduate and graduate student and as a professor, many of my major life changes have often occurred at the beginning of the academic calendar year, which usually corresponds with the start of the fall semester in August or September. So, Dude Mountain has become my reset for each academic year, a way to officially transition from summer break into teaching again, a time for me to internally reflect on the positives and negatives of the previous year and to set my intentions for the upcoming year, when sometimes I hike alone and sometimes friends join me. I didn’t set out for Dude Mountain to become my new-year hike; it just sort of evolved into that. Perhaps because September is my favorite month for hiking in the Ketchikan alpine—the least amount of snow and bugs. The weather is generally a little cooler and the days can often be sunny too.

The drive out to the trailhead is one of the most scenic drives that Ketchikan has to offer. Starting from downtown Ketchikan, the drive can take about forty to fifty minutes to the trailhead. The second part of the drive is a blacktop road that turns into a dirt backroad through a mountain-rimmed valley that leads toward the interior of the island, where one can continue on to George Inlet or spoke off to Harriet Hunt Lake or up Brown Mountain Road, where the trailhead to Dude is. Brown Mountain Road is our only true twisty mountain road that climbs up into the high country vistas that is popular with weekend sightseers, hunters, wood and berry gatherers, and hikers. Brown Mountain Road dead-ends at the National Forest Service’s Dude Mountain trailhead. Squarely placed within the Tongass National Forest, Dude Mountain is one of the quickest ways, on foot, to reach the alpine tundra. From the trailhead, it is a 1.5 mile climb up 1500 feet. Depending on one’s pace, the climb can take up to two hours or more, one way. There is generally no cell-phone service (until the top and even then not always a guarantee), so it’s important to bring warm clothes, rain gear, flashlight, and plenty of food and water as the weather can change quickly in Alaska and in the mountains.

The trail starts out gravel and winds its way up to boardwalk through the lush rainforest and the beginning muskeg meadows above and then turns back into gravel in the alpine. The last part of the hike is steep and can be muddy in wetter weather or covered in snow depending on whether one is hiking in spring or late fall, so a trekking pole or two can be useful both on the ascent and descent. Once the big snows fall, Brown Mountain Road is only accessible by snowmobile. Usually June into October offers a snow-free ascent. Just before the last part of the climb, the trail pops out onto a ridge between two valleys with clear views of John Mountain to the left and Brown Mountain on the right and the Tongass Narrows beyond if it isn’t cloudy. And of course one can see Dude Mountain’s summit right ahead. The ridge leads to the face of Dude Mountain, which is exposed and steep, but isn’t considered a rock climb. Generally, with careful, slow placement of feet, one can step up the rutted-out dirt path filled with rocky steps. Once atop the face, follow the trail to the right and cut up and into the krumholtz to the summit proper. On this brief last stretch, there can be knee-deep mud holes here and one can find a small camp-sized clearing that overlooks Brown and Diane Mountains and the Tongass Narrows to the north and west. However, I usually forgo the summit proper and instead find a perch in the alpine anywhere below and to the left of the krumholtz and enjoy the ridgeline of Diana Mountain to the right and the whole ridgeline to the left across the valley that houses Deer Mountain, Northbird Peak, and John Mountain. And of course the Dixon Entrance that floats beyond Annett Island and the Percy Islands into the great Pacific Ocean.

I’ve seen goats and ptarmigan on this hike. I’ve heard other hikers talk about The Lady of the Mountain, a supposed two-foot tall brass statue that hikers like to look for and continually move around for the next hikers to search for. But for me, I’m searching for silence and peace, so I like to choose a day when there aren’t any float planes buzzing around, like one year when coincidentally it was also Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. My girlfriend and I hiked to the top and she received a phone call from her mother who lives in Florida, wishing her happy new year. After the phone call my girlfriend was very chatty with me, but I had to tell her to please be quiet, something amazing was happening. And then I was struck, as if a toneless bell, by the deep and profound silence of the ocean and the mountains stretching all the way into Canada. The land was speaking to me, and I connected so deeply that I was moved to tears because the moment was so beautiful and unexpected. And then out of nowhere, on this very still day, a little tornado of a wind whipped up right by me and disturbed a very small tarn before me as if there were a salmon about to breach and then the disturbance was gone. I may not have seen her yet, but that day, I was blessed and felt the presence of The Lady of Dude Mountain.

Lower & Upper Silvis Lakes and Mahoney Mountain (3350 ft.)

- 4-6 miles round-trip (3-4 hours)

- 1112 feet elevation gain

From downtown Ketchikan, 13 miles south on Tongass Hwy until you dead-end into a gravel parking lot with dam-related out buildings.

- 2 miles one-way to Lower Silvis Lake (1.5 hours)

- 3 miles one-way to Upper Silvis Lake (2 hours)

- 6 miles one-way to Mahoney Mountain (6+ hours) 3300 feet elevation gain

My girlfriend and I and a friend decided to take a three-day weekend to attempt the Deer Mountain to Silvis Lakes Traverse one September. None of us had done it before. I’d been as far as Blue Lake from the Deer Mountain side and as far as Upper Silvis Lake on the Silvis side. I wasn’t too keen on doing the whole 14-mile trek in one day, and thought I’d rather break it up over a few days and bring camping gear. But after the first day of hiking in the mountains with nearly a fifty-pound pack, I wasn’t too keen on that idea either, so we altered our plans and decided to camp below the Mahoney Mountain summit and spend an entire sunny day there before we hiked back out.

Located in the Tongass National Forest, the Lower and Upper Silvis Lakes Trail is a two-and-a-half-mile access road for the Ketchikan Public Utilities company so that they can maintain the hydroelectric dams on both Upper and Lower Silvis Lakes. The road is gated and locked at the parking lot, but people are welcome to hike the steep road to Lower Silvis Lake. At first, the road is a series of switchbacks, and then it eventually follows a creek on the right that drains out of Lower Silvis Lake. At times, you will walk beside the black waterline that pipes the water down to the Beaver Falls Powerhouse. You will walk across a recent landslide patch where the road’s been cleared again. Next, you will come to a small dam house on the right, where you can walk up to the river and see where there once used to be a spectacular waterfall here. Looking south from the waterfall, you can see snowcapped mountains in the distance. Continuing on, you will come to an outhouse on the right where the road begins to slope down to Lower Silvis Lake. You will find some picnic tables on the left and you can also hike down onto the top of the dam where there is also a picnic table here. Looking down the length of the lake, Mahoney Mountain dominates the entire scene, from its peak towering above the head of the lake to its ridges that wrap around the entire length of the right-side of the lake and beyond. This road is often very shady as it is difficult for the sun to reach this deep and tucked-away valley.

The service road continues on for another half a mile along the shore of Lower Silvis Lake and below the steep mountain sides of Twin Peaks and terminates at another powerhouse, where you need to cross a bridge over the creek being fed from Upper Silvis Lake. Here is where an actual foot trail begins a half-mile hike up through the woods to Upper Silvis Lake and is also continues on all the way to Deer Mountain. The trail finishes by crossing a wooden bridge into a rocky area that looks like it used to be a waterfall flowing out of Upper Silvis Lake, and here you ascend these rocky steps up to the top of the Upper Silvis Lake dam. Upper Silvis Lake is a beautiful lake rimmed with mountains—Twin Peaks, Achilles, and Mahoney Mountains. If you are continuing on, this is a good place to go down to the lake and refill your water bottles with whatever water-treatment system you have. The lake can be accessed around to the left.

Continuing on to Mahoney Mountain, we found the trail newly improved with fresh gravel and stone steps as we followed the northern shore of Upper Silvis Lake. Then the trail began to climb away from the lake and wind up a broad ridge. Eventually the improved trail petered out and the bushier and more rugged unimproved trail began, which was still easy enough to follow. However, sometimes the trail would split and we’d choose one path only to find what seemed like the other path rejoined again. As we gained elevation, the forest began thinning and we walked through some small clearings. Late in the day we found ourselves above tree-line walking through a high and narrow valley bottom with Mahoney’s rocky ridges jutting up around us. We followed the trail into a bowl of boulders and a creek and hiked up to a loft-like ridge where we made camp where it overlooked the bowl and the small valley we just hiked as well as the summit of Mahoney Mountain above. From this camp, we could also see George Inlet and the mountains beyond. We were probably less than a mile from the summit and a good 1000 feet yet. Here the trail continues upward to either the summit or to continue the traverse to Deer Mountain.

That night at camp while we were eating and the light was dimming, a group of people were hiking down the mountain having started from Deer Mountain. An older woman was in bad shape, her ankles were swollen and giving out on her and a man was holding here hand and guiding her down the rocky path really slowly. We filled up their water bottles for them and my friend gave the woman both of his trekking poles and told her to leave them under his car at the trailhead. They had a long way to go yet and it would soon be dark. Luckily, they said they were able to gain permission to have someone drive in to the end of the access road to pick them up. But they still had a few miles to go yet. Looked like a disaster about to happen. But we had no room for them in our tents.

The next day was gloriously sunny and warm. I staid back at camp and rested, read, and took in the scenery while the other two went up the trail a little further. The traverse would have to wait for another day, and doing it in one day while traveling lightly was looking more appealing to me now. But in the meantime, I was happy to be camping on the mountain with friends rather than blowing past it all in one day.

Lunch Creek

- 9.6 miles round-trip (6-8 hours+)

- 1300 feet elevation gain

From downtown Ketchikan, 18 miles north on Tongass Hwy until it dead-ends at the trailhead.

My first date with my girlfriend was hiking the Lunch Creek Trail on Memorial Day. We had just met the Friday before at our mutual friends’ dinner party. Years later, looking back on that dinner, we wonder if they were trying to set us up, but they deny any intention of that. After the dinner, I felt I had to ask her out soon in order to better establish a connection because I was off to Boulder, Colorado for a week beginning the following weekend. The Lunch Creek Trail’s ten-mile round-trip to Lake Emery Tobin became my perfect excuse to spend a day together getting to know one another better.

What’s nice about the Lunch Creek Trail is that it is all the way out north where the road dead-ends and is absent of homes and motorized traffic, except for the quite turn-off of Settler’s Cove Campground, where Lunch Creek pours into the Tongass Narrows. The Lunch Creek trailhead swings to the right. If one goes left, the trail will lead them to a waterfall platform and down to the ocean and will join The Lunch Falls Trail, if taken to the right, which is approximately a 0.5-mile loop. But Lunch Creek Trail follows along Lunch Creek up a ladder of many beautiful waterfalls right away. Some of my favorite large trees stand guard on this trail—western red cedar, hemlock, and Sitka spruce so large that I often feel the need to bow to these surviving elders when I pass.

Once the stairs are climbed not far into the hike, the gravel trail levels out for a while as it traverses land owned by the Alaska State Parks. About a mile in, the trail turns to dirt, roots, and stones when entering the Tongass National Forest at a nice sandy river bend where a sign reminds us that we are in bear country. Others think there are more than bears to be aware of, especially out on Lunch Creek Trail. Once I hiked this trail with a man who tried communicating with Big Foot by whacking a large stick against a spruce in choppy patterns, and we listened for any knocking responses off in the distance. I didn’t hear any. But one time coming back from the long hike with another friend as the evening began to darken in late winter, when I thought the bears were hibernating, we heard a low, spooky moan of a very large animal echo through the river valley.

Continuing up the valley, the trail becomes boardwalk over a couple muskeg sections, where one can see the towering ridge on the other side of the river, then begins to climb into the forested hillside away from the river, crosses some small streams, and eventually comes back down to walk along the river side once again. Next the trail crosses a bridge to the other side of the river for the first time. Boardwalk steps begin the more serious elevation gain now, which soon leads you to an intimate perch beside a waterfall, where I’ve seen American dippers repeatedly dive into the rapids to feed and pop back out onto a rock. This is a nice place for lunch and rehydration and where one can refill a water bottle if equipped with a proper backcountry water filter or water-treatment system.

The trail continues to climb alternating between boardwalk steps, a rooty dirt trail, and sometimes muddy holes, which lead to a level boardwalk across a muskeg field. Eventually the boardwalk leaves off to just muddy footprints trammeled through forested muskeg lanes, climbing onward until one ends up at the headwaters of Lunch Creek—the shores of Lake Emery Tobin, which is surrounded by a rim of steep mountainsides often capped with snow ridges and peaks. When my girlfriend and I on our first date arrived at the lake, the last stretches of muskeg and the lakeshore were still covered in snow late in May. We spread out our rain pants to sit down, tugged on our fleece jackets and winter hats, and shared cups of green tea as we got deeper into our histories and past relationships, the lake all to ourselves. Soon we became more comfortable with the space between our words and stories, more comfortable with the ringing meditative silence that the snowy peaks and rainforest continually emanated until we felt we no longer had to say anything at that moment and could just be together, quietly sipping tea, watching our breath, happy to be alive and able to share in this beautiful and solemn place. Such an auspicious beginning to our budding friendship then, and now several years later, a significant marker of how far we’ve come on our continued path together, always making sure to revitalize with tall drinks of wilderness in order to cultivate healthy space and time for one another.

Minerva Mountain

- 4 miles one-way, but combined with the Perseverance and Carlanna Lake trails, ≈ 8 miles one-way (8+ hours)

- 2600 feet elevation gain

Perseverance Trailhead: From downtown Ketchikan, 6 miles north on Tongass Hwy to Ward Cove...

Carlanna Lake Trailhead: From downtown Ketchikan, 2 miles north on Tongass Hwy...

Perseverance Trailhead: From downtown Ketchikan, 6 miles north on Tongass Hwy to Ward Cove. Right on Revilla Rd. for just over 1 mile. Right on Ward Lake Road for 3/4 mile. Just after your cross the Ward Creek bridge, turn tight into a parking lot across from the Three Cs’ campground. To access the trailhead, cross the road and continue down the road about 100 feet. The trail will be designated by a sign on your left.

Carlanna Lake Trailhead: From downtown Ketchikan, 2 miles north on Tongass Hwy. Right on Carlanna Lake Road until it ends. Right on Fairview Ave. until it ends. Right on Canyon Road, which will soon dead-end in a small dirt parking lot. Begin hiking up the gated road to the dam, veer right to access the trail.

After a Saturday night of a few beers, a pallet bonfire, and sleeping out under the stars on South Point Higgins Beach, Sunday morning three friends and I decided to hike the Minerva Mountain trail, locally known as the Carlanna-Perseverance Traverse, which is located in the Tongass National Forest. We first stopped at one friend’s house, where he baked us a Spanish omelet and plied us with coffee as we stored up protein and wakefulness for the hike before us. The Minerva Mountain Trail begins at the end of one of two trails that it connects: either 2.5 miles at the end of the Perseverance Trail at Perseverance Lake or 1.5 miles at the end of the Carlanna Lake Trail.

A warm, sunny day, the first thing we had to do was to drop off a car at the Perseverance trailhead, where we’d finish the one-way trip, and then I drove everyone to the Carlanna Lake trailhead, where we’d start. About an hour into our hike, we picked up the Minerva Mountain Trail when we crossed the creek, which drains into Carlanna Lake, at the bottom of the Avalanche Chute. Here, we picked up the new and improved trail that was carved out of the forested hillside and filled with crushed gravel and nicely planted flathead rocks as we hiked our way up and across the side of Minerva Mountain. We soon found ourselves at a nice waterfall and pool that overlooked the valley, where we filled our water bottles and rested a little.

Continuing on, we then came across a man we knew and his hyper but friendly yellow lab keeping him company along with the radio. Hired by the National Forest Service to build the improved section of trail, he hiked in and out every day just to chainsaw downed trees, dig out the trail from the slope, and move large rocks in or out of the way. He took a break from winching a massive rock out of the path and wiped the sweat from his brow, his shirt stained wet down the middle of his back and around his neck. We caught up for a few minutes, thanked him for the awesome trail, and then he was back to work and we began the slog through the unimproved trail.

In another twenty minutes, we began popping out of the forest into a giant rock-slab slope dotted with vegetation clumps. Here you need to keep an eye out for the orange diamond markers where you can find them and then cairns higher up, marking the path to the gap between Minverva and Juno Mountains. Once you gain this treeless ridge, the other side drops off 1500 feet or so into Perseverance Lake. Beyond that, you can see Connell Lake and then distant mountains. To the right continues Minerva Mountain, and Diane Mountain ridge boxes in the right side of Perseverance Lake. Behind you is the Tongass Narrows and Annette Island, Gravina Island, and Prince of Wales Island. To your left, is the summit of Juno Mountain.

The trail, now a dirt path through low vegetation, continues to step up to summit Juno Mountain and then quickly dips down into a saddle between Juno and Ward Mountains. Here we met two women who were completing the traverse in the other direction. We took a few of minutes to say hi and to share the trail conditions we had both completed. Soon after our goodbyes, we found a lovely place for lunch tucked in just below Ward Mountain with views of the Tongass Narrows and accompanying islands. We sat down beside an old fire pit from someone’s once overnight camp and shared a light lunch of grapes, crackers, cheese, sausage, bell pepper, and hummus.

After lunch, we began our descent but then somehow, we found ourselves off the trail. We seemed to be skirting just under the peak and facing dense alders and a drop off. We decided to veer right and pushed our way through the alders until we popped back out on a descending rock-slab lane where we found the orange markers of the trail again. Here on the shoulder of Ward Mountain, we continued to switchback through a high alpine muskeg for a while and enjoyed the great mountain and ocean views that stretched to the north. Eventually, the muskeg trail ended at a lengthy boardwalk that stepped down ridge of cedar and spruce all the way to Perseverance Lake. Once we reached the lake, two of my friends hightailed it down the Perseverance Trail for the last two-and-a-half miles back to the car in order to quench their thirst by getting a jump start on the beer in the cooler.

After we made it back to the car, we drove back around the mountain ridge to the town side where we picked up my car at the Carlanna Lake trailhead. Properly famished, we promptly went out for pizza and beer. We later bookended the glorious day with another beach bonfire and sleeping beneath the stars, but this time—as if we had reached into the Juno Mountain sky earlier and stuffed them into our packs just to let them out right now—the aurora borealis danced and shimmered, happy to be free in the Alaskan sky once again, like we had felt earlier on the Minerva Mountain Trail traverse.

Perseverance Trail

- 5 miles round-trip (3-4 hours)

- 450 feet elevation gain

From downtown Ketchikan, 6 miles north on Tongass Hwy to Ward Cove. Right on Revilla Rd. for just over 1 mile. Right on Ward Lake Road for 3/4 mile. Just after your cross the Ward Creek bridge, turn tight into a parking lot across from the Three Cs’ campground. To access the trailhead, cross the road and continue down the road about 100 feet. The trail will be designated by a sign on your left.

Popular with the locals and located within the Tongass National Forest, Perseverance Lake is one of my favorite trails and is a great Saturday or Sunday morning or afternoon hike. Before this trail received a facelift a few years ago, much of it stepped through the rainforest valleys as a boardwalk path. Because of the years of wear and weather eroding the boardwalk, some sections were off kilter and sliding toward a creek valley or had loose or missing boards where you’d have to watch your step. This is one of the trails on which I take most people who come to visit me: my youngest sister, a second cousin once removed, a past girlfriend, and a 70-year-old qigong and tai-chi master. Once a friend of mine had contacted me to let me know that her friend’s family had brought her on a Southeast Alaska cruise and would I take them all hiking when they got to Ketchikan? Of course; I was so thrilled that she had looked me up and that I had another opportunity to hike with her when I thought I’d never see her again. I had met her in Ketchikan when she was a traveling nutritionist and, before she moved back to California, we would often hike together. I loaded up my Subaru Forester with these 5 extra people, even placing one in the way-back, and drove them out to hike Perseverance.

The Perseverance Trail leads up and away from Ward Lake and starts on the south side of Ward Creek, heading toward Connell Lake. The gravel path slowly and steadily climbs through the dense rain forest and crosses over a few bridge-spanned creeks. Eventually, you walk through a couple small muskeg flats and then the trail cuts into the hillside above a small creek valley below. The trail swings left to climb up to skirt the edge of a pond, then swings right to walk through the edge of another small muskeg field. Soon the trail steepens through the forest again, then switchbacks left as you climb out of the valley into a less dense forest. Switchback to the right, you climb into a brief muskeg opening, swing left back into the trees. Switchback right again and you are on the final stretch to the lake. Here you are above another valley on the left where a creek drains out of Perseverance Lake and into a waterfall that tumbles down the creek to flow into Connell Lake, which you can sometimes glimpse through the trees. Walking on, you will hear the waterfall get closer and see it through the trees off to the left. Soon the trail will turn to boardwalk in a small muskeg field and just a little further, you will reach a fork in the trail.

Straight ahead the trail crosses a bridge over the headwaters of the creek and continues on for about a quarter mile along the creek to terminate at a tent platform on the north end of Perseverance Lake. Here you can see a clear view of Juno and Minerva Mountains on the other side of the lake and Diane Mountain to your left. Many large trunks of driftwood cedars and spruce are gathered here like a tangled raft of haphazard docks. Back at the fork, if you take the trail to the right, this is the beginning of the Minerva Mountain Trail, which steps up Ward and Juno Mountain and down into Minerva Mountain to descend to the Carlanna Lake Trail. About a half mile up this trail is another lakeside tent platform, which can be accessed by what looks like a deer trail through the vegetation. This platform is perched many feet above the water and provides an intimate view of Diane Mountain.

Sometimes before work in the early morning, I would take an hour and run up to and back from the lake and then swing by the old pool for a cheap shower before I taught class. I was often the only one on the trail at that hour of the day during the week, and I’d have the lake all to myself. The best mornings were when the lake was still and mirrored the mountains and a lone loon’s call would greet me.

Rainbird Trail

- 2.6 miles round-trip (1-2 hours)

- 300 feet elevation gain

From downtown Ketchikan, 3.5 miles north on Tongass Hwy. Right on Jefferson at the second stop light. Straight up the hill.

Trailhead 1: Last left onto Madison Street, which dead-ends at the University of Alaska Southeast (UAS). Enter UAS’s parking lot and park in the far-left lot near the back of the Ziegler building. Trailhead is here. Trailhead 2: Turn right off of Jefferson onto 3rd Ave. After the last stop sign, there will be a parking lot on your left. Park here and take the stairs up to the middle of the trail. Trailhead 3: A little further beyond trailhead 2 is the other end of the trail, where there is a small gravel spot on the left to park beside another stairwell to the trail.

The Rainbird Trail has long been my Friday-after-work walk. One end of the trail begins at the University of Alaska Southeast’s upper Ketchikan campus, right where my office is. Setting out on the trail right at 5:00 pm on a Friday has been a healthy way for me to immediately transition from the week’s arduous professorial work into the weekend of time off. If the week had been a particularly stressful one, it may take me both lengths of the trail out and back before I am able to let go of work and for the most part, calm my mind down to the here and now of my breath, my footsteps, and actually hear the refreshing waterfalls and smell the damp pine boughs about me. I refer to this as the town trail because it hikes above a stretch of Tongass Hwy where many businesses are and neighborhoods. Often float planes can be heard taking off or landing and the testosterone-laced boy or man stepping on his loud truck’s gas pedal. But the trail is rugged and beautiful as it steps through cedars and spruce along the lower reaches of a mountain side.

The Rainbird Trail was spearheaded by the UAS Ketchikan Trail Improvement Project, which partnered with the Ketchikan Gateway Borough, the Rasmuson Foundation, UAS Alumni & Friends, Wells Fargo, and the Southeast Alaska Trail System plus many other organizations and individuals who generously donated to this project. Beginning at the college, the gravel trail crosses over a bridge and creek and quickly ascends in an S curve, with some log steps at the top of this section. Here another bridge crosses the creek again and begins to flatten out for a short section through an alder grove. Then the trail begins to climb again with the hillside falling away through the forest off your right. At the top of this section, the trail descends into an unimproved section that is filled with roots, rocks, mud, and small standing pools of water. Just around the bend, you will cross another creek without a bridge and climb up a root covered section of trail. Stay to the left in order to stay on the trail and you will soon cross another bridge where the improved trail begins again. From here, much of the trail is laid out in large flat stones and soon joins the middle trail that steps down to the trailhead 2 parking lot.

Continuing on, the trail cuts and winds through the slope where you’ll duck your head beneath a downed spruce trunk and descend a little on large flattop rocks that look almost as if they are chunks of petrified trees. Soon the trail will turn to gravel again and begin to climb to a drop-off overlook of this northern section of town stretched out along the narrows. A crude wooden fence walls off the trail from the drop-off here. This is a great spot to soak up any sun that may be out and to watch the hustle and bustle of town below—the cars driving along Tongass Hwy, any boats and float planes coming and going, the occasional Alaska Marine Highway Ferry or cruise ship, or an Alaska Air Boeing 737 taking off or landing. You can see from the northern end of the airport runway to the southern channels beyond Annette Island. Quite the panoramic view where I like to lean against the fence rail and just soak it all up for fifteen or twenty minutes before turning back around.

However, the trail does continue on just a little further for a partial view of Deer Mountain and downtown Ketchikan, where up to four cruise ships can be seen docked. Then the steps take you down to the final trailhead on 3rd Avenue. A great trail that can be easily accessed from town or for when you don’t have much time for a longer excursion and still would like to get out for a little exercise and nature.

Ward Creek

- 5 miles round-trip (2-3 hours)

- 100 feet elevation gain

From downtown Ketchikan, 6 miles north on Tongass Hwy to Ward Cove. Right on Revilla Rd. for just over 1 mile. Trailhead 1: Right on Ward Lake Road for 0.5 mile. Right into a parking lot. Cross the road, by the entrance to the parking lot, and pick up the trail here. Trailhead 2: ...

Continue on Revilla Rd. for a couple more miles until you come to a small parking lot on the right with an outhouse. Trailhead 3: About a half-mile past Trailhead 2 is Last Chance campground on the right. The trail can be found on the river towards the back of the loop. During the months of October through April, the entrance to the campground is gated and locked, but one can still park and walk from here.

From trailhead 1 at the Ward Lake parking lot, Ward Creek became my go-to trail to run after work in the spring and fall because it was on my way to and from work. Located in the Tongass National Forest, Ward Creek is wide enough to drive a truck down, though no vehicles are permitted. I would go so far as to say that this trail is wheel-chair accessible because there are no steps in this even, gravel pathway, though there are some hills. For the most part, the trail follows Ward Creek, which flows out of Connell Lake, by the Last Chance campground, and through Ward Lake and eventually into the ocean at Ward Cove.

Ward Creek is popular with the locals for walking dogs. My sister, her husband, and I sometimes would dig out our flashlights and walk here at night in the fall and wintertime with their two American bulldogs and a Tibetan mastiff. The trail winds through the lush rain-forest and climbs above the creek that flows steeply below, where you can hear and see the whitewater. Occasionally, you can glimpse Brown Mountain through the trees on the right. Along the way, three short spurs lead to decks perched on the creek. Here people can fish, or just watch the river, or sometimes watch black bears catching salmon in the late summer and early fall. The trail skirts besides a couple of muskeg fields on the left where one can see a mountain ridge. Just after crossing a bridge and ascending a small hill, a rock wall on the left of the trail would sometimes glimmer in the sun. Upon a closer look, someone had gently wedged in pennies, quarters, nickels, and dimes randomly throughout the face. It would seem that we had our own cliff version of a wishing well. Outhouses are available at the Ward Lake parking lot, the trailhead 2 parking lot, which is about two miles away from the Ward Lake parking lot, and at the Last Chance campground, which is just another half-mile from trailhead 2. Occasional backless, trail-side benches are available, where one can rest or just meditate on the river below. For extended walking, this trail connects to the Pipeline, Salvage, and Ward Lake trails. One winter storm, enough snow fell where I could actually cross-country ski the trail. Downy puffs of snow weighed down the pine boughs and whitened up the green landscape. Reminded me of skiing back home in northern Michigan, a rare treat here.

At the far end of the trail on my runs, I would circle through the Last-Chance campground loop before heading back down the trail. Here in the summer season, I would note the comings and goings of new campers and reminisce about my camping excursions. One season, one particular camp caught my eye because of the semi-permanent setup that sprawled across two camp sites with multiple two-man tents. A large canvas wall-tent opened up to two picnic table with a couple two-burner, propane stoves and coffee cans. I wondered if this wasn’t where the young and bronzed, chap-wearing, chainsaw-slinging, weed-whacking trail crew stayed with their overgrown 4x4 van. I had run into them earlier that season out on the Connell Lake trail and they worked in unison like a sharpened, well-oiled chain buzzing down the trail, away from the hive. So, if you ever run into these folks out on the trail, make sure to let them know how much you appreciate them keeping the trails maintained for our enjoyment. These are our unsung heroes and heroines carving the way into our backcountry bliss. And just like the rest of us, a little appreciation can certainly go a long way because working this gnarly country can kick your butt and the meager offerings of compliments can be too few and far between. Because of them, during most times of the year, this is a great trail for a weekend-afternoon walk with your loved one. Easy to walk side-by-side, hold hands, and talk, or to just walk in comfortable silence together and listen to the river’s ceaseless babbling about its short but lively journey from lake to ocean shore.

Wherever I have lived, I’ve always had a stock, go-to walk that was a no-brainer for just getting me out of the house for some quick, maintenance exercise in the woods for some peace-of-mind. That walk for me in Ketchikan has become Ward Lake. I decided to establish a morning routine to walk Ward Lake on my way to teach at the university, no matter the weather, instead of just rushing off to work first thing. Not only did this help to set a relaxing tone for the day, but I was able to connect with and observe the small nuances as well as the big changes in the seasonal weather and wildlife habits. One late February, I was tipped off to an early spring when a pair of swans with two cygnets foraged along the shore of Ward Lake, and the honks of geese returned as they landed in the lake for a needed rest during their migration back north. But one of my favorite returning sounds of the wild is the solemn call of the loon. I always know I am in a good place when I hear loons. Reminds me of my times canoe camping in northern Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area and in upstate Maine.

Managed by the National Forest Service, Ward Lake is just tucked into the edge of the Tongass National Forest boundary. This area used to once be a Civilian Conservation Corps camp in the 1930s and also housed relocated Aleuts during World War II. Informational signs are posted about this history at the Ward Lake beach and the nearby Three C’s Campground, and remnants of stone foundations from these camps can still be found. Because of Ward Lake’s close proximity to town, the area is a popular place with the locals. Three shelters, complete with fire places, picnic tables, grills, and horse-shoe pits, dot the beach area right beside the parking lot where an outhouse is available. There are a handful of other picnic sites along the lake that pull-off from the road. In the summer season, a water pump offers fresh drinking water. The mostly flat trail follows the circumference of the lake’s shore in a swath of gravel that is wide enough for two people to walk abreast. The trail crosses two bridges over Ward Creek, which runs into the east end of Ward Lake and out the west end. The lake and creek are scenically placed in a valley of mountains. Most dominant are Brown Mountain and the Diane Mountain ridge. In the winter, if the lake freezes, one can find many people sliding and skating on the ice. Within walking distance are also three other trailheads: the Ward Creek trail can be picked up on the other side of the Ward Lake parking lot and road; the Perseverance Lake trail lies further down the road just over the Ward Creek bridge, and the Frog Pond trail can be accessed where the road dead-ends at Signal Creek Campground.

Early spring or late fall mornings, sometimes the air is colder than the water and a mist glides across Ward Lake to rise and form a small cloud. Eagles, seagulls, herons, mergansers, mallards, and kingfishers frequent these waters. It’s not uncommon to see large piles of back-bear scat plopped right in the middle of the trail. I’ve seen a family of otters playing and eating among the shoreline reeds. Along the trail, one can also find informative signs about the flora and fauna in that area. In the spring, fly-fisherman wade off the east banks of where Ward Creek flows into the lake and where in the fall, I like to watch the salmon migration swimming up river to spawn and die. And I’ve just discovered a well-hidden beaver home, which I’ve walked by hundreds of times, because I was tipped off by the fresh beaver shavings littered around stumps of missing alders this time.

What’s fun about Ward Lake is that because it is fed by rivers that capture all the rain and snowmelt from the surrounding mountains, the lake level can rise and fall dramatically, sometimes flooding the south-side of the trail. In this case, the road can be walked. I like to check the water levels under the west-end bridge where the creek flows back out of the lake and a large boulder in the river shows where the water is on its back, which is completely exposed in low water and completely submerged in high water. This part of the river can have two- to three-foot standing waves in extreme high water.

At the west-end of the lake, the trail meanders through Signal Creek Camp-ground, where Signal Creek enters the lake. Rural campsites perch on the lake and along the creek, offering picnic tables, fire rings, and bear boxes to store food. This was my first home in Ketchikan for about a week when I first arrived with my father several years ago, having driven across the country from Michigan. My sister who’d already been living in Ketchikan for many years, her husband, and a friend came out that first night with firewood and beer to welcome us to town. We laughed, told stories, and enjoyed being reunited as we lit up the giant trunks of Sitka spruce with sparks of our warmth dancing with our fairylike shadows. For all of these reasons, I like to continue returning to walk Ward Lake in order to remind me of the never-ending cycle of change, of birth and death, and that I am a part of it, which helps me to practice being present in the moment because each step of the way is a precious gift of time we should not waste.

Whitman Trail

- 1.4 to 2.2 miles round-trip (40 min-1 hour+)

- 200 feet elevation gain

From downtown Ketchikan, 8.6 miles south on Tongass Hwy. Parking on the left-side of the road. You will see a large green sign with the hiking symbol of two hikers that reads “Whitman Trail” with an arrow point to the right of the parking lot where the trailhead begins at the gated gravel road.

- 0.7-mile to Whitman Lake Dam (20-30 min)

- 0.8 mile to Achilles Creek Diversion (20-30 min)

One sunny, Sunday afternoon in February, my girlfriend and I were having a random day and after a late breakfast in town and then walking along the Tongass Narrows where we could soak up the warming sun out by Mountain Point, we decided to drive to the south end of the road but happened upon Ketchikan’s newest trail by chance—the Whitman Trail, so we decided to check out. Much like hiking the access road to Lower Silvis Lake, the Whitman Trail is another service road to two dams that generate electricity for Ketchikan residents and was recently made available for hiking and recreation; however, no motorized vehicles are permitted. Informative signs are posted on a fence gate up the road and on both dams. We decided to check out both dams and walked up the road enjoying the new variation on the theme of mountains, forest, and muskeg.

About a half-mile up the road, you come to a fork. We went left and followed the switchback to the right where we came to a flat, gravel platform where we found a picnic table overlooking the service road in and the sunny mountains on the other side of George Inlet. From here, we walked the shady road where Whitman Creek flowed to the right and soon the road dead-ended at the Whitman Lake Dam. According to a sign here, the Whitman Lake Dam has been a dam since 1908 when it was built out of logs. Then in 1926 it was rebuilt with concrete. Unfortun-ately, there is no public access to the top of the dam where one would hope to get a glimpse of Whitman Lake. Instead, we had to be satisfied with the picturesque ridge between Deer Mountain and Northbird Peak poking up from the lip of the dam, all lit up in sun.

We walked back down to the fork in the road and ventured up the right arm, where we crossed over Whitman Creek and began following Achilles creek on our right until the road dead-ended again at the Achilles Creek Diversion Dam. Here the small creek dam was high enough to just be lit up by the late-afternoon sun, yet still cold enough that the lip of the dam was still a frozen waterfall. Here a sign shares some more history of the multiple uses of this water for power, drinking water, and the salmon hatchery.

On the way back down the trail, we enjoyed the scenery in reverse, this time taking in the distant entrance to George Inlet and the mountains across the water. We were glad for the novelty of experiencing this new trail for us, grateful for a change in scenery, and as always, just to get outside and enjoy each other’s company on a Sunday off.

Ketchikan Weather

Mostly we get rain, up to 160 inches a year, from an indistinguishable solid mass of clouds that shed a range of precipitation: threatening rain, having just rained, on-and-off drizzles, soaking mists, steady rain, sheets of rain, and sideways sheets of rain (with strong winds). And sometimes it just rains. It can often be raining in town and sunny out north or vice versa, and rainbows can appear in the transitional zones. On the rare occasion, we’ll get a thunder storm, but we’re talking maybe once or twice a year, and often never in a year or two. However, experiencing many different types of weather within one day is possible at any time in Alaska, especially when you are hiking into the alpine. You may start off with sun and high 60s or low 70s at the trail head near sea-level, may hike into rain halfway up the mountain, and then run into snow near the top of mountain. If you can’t see the top of the mountain because clouds obscure the peak, that most likely means that it is raining or snowing up there. Sometimes the opposite can be true as well. You can start off in cold rain at the trailhead and then pop out above the clouds into the sun. Occasionally we’ll get sleet and hail too. And the lake and river temperatures are usually quite cold because they are often fed by snowmelt from the upper reaches of the mountains. Our ocean here is also very cold too. According to the United States Geological Survey of the Ketchikan area, in the summer the water temperatures can range between 50 and just over 60 degrees Fahrenheit and in the winter can get down as cold as 32 degrees Fahrenheit.

The summer air temperatures can range from 50s to the 70s, with occasional dips into the 40s and spikes into the 80s. The fall and spring are generally stuck in the 40s, and the winter usually hovers around the 30s to low 40s, with high-pressure dips into the 20s and sometimes teens. I have seen the temperature drop into the single digits before. If and when we get snow in the winter, it usually happens as a colder arctic high pushes out the usual rainy low and the rain changes to snow and drops heavy and wet anywhere from a couple inches to a couple feet. Then we’ll have sun for a few days or couple weeks and temperatures below freezing, preserving the snow. When the low-pressure system moves back in the from the south, we’ll usually get more snow as the arctic high leaves, but then as the temperature gradually warms up, the snow turns to rain, washing the snow away once again.

Another thing to be aware of is wind. In the alpine area above tree-line, you are more exposed to the elements because there is less shelter and the mountains can create their own weather. In the early afternoon, the land heats up during a sunny summer day, and the colder ocean air will be drawn toward the land as the hotter air rises. Because of the mountains here, the higher elevations will also usually be colder due to snow and being a higher elevation, and this colder air will sink as the sea-level land’s warmer air begins to rise. These inversion winds can range from a light refreshing breeze to some erratic stiff winds. Besides these local winds, the larger weather patterns can change quickly here because we are perched right on the eastern end of the Pacific Ocean, where nothing slows the jet-stream down as lower-pressure systems gain momentum, moving from west to east across the open expanse of the Pacific. Ketchikan is known for forty- to sixty-mile-an-hour winds, and on occasion up to 100 miles-an-hour in a rare, extreme storm, usually around the equinox in the spring or fall. These winds are sometimes referred to as Taku winds, where a cold high-pressure system moves down into Southeast Alaska from the arctic, pushing out the regular rain from the warmer Japanese Current. I’ve woken up to the sound of my neighbor’s propane grill being hurled off his deck to crash into our driveway. And trees blow down across roads and knock the power out. Though summer is usually quieter in general, the winds can kick up. One day in 2016, the wind was up and for the first time a cruise ship came into the city docks too hot and took out berth 3. So, be forewarned: the weather is no joke.

Day-Tripping Gear

Recommended

- Backpack (always good to line the inside with a small garbage bag to keep contents dry or purchase an appropriate sized exterior cover that is waterproof)

- Rain jacket and rain pants (Gortex-type of material is light, packable, and breathable for activity)

- Fleece or jacket

- Food and water

- Map and compass or GPS with extra batteries

- Cell phone (recommend kept in a small dry bag or zip-lock bag)

- Emergency space blanket and tarp in case you have to spend a night in the woods

Optional

- Hat and gloves

- Flashlight with new or fully charged (and extra) batteries

- First-aid kit

- Matches or lighter

- Toilet paper and small garden shovel or toilet paper and a Wag Bag

- Sunscreen

- Camera (recommend kept in a small dry bag or zip-lock bag)

- Trekking pole(s)

- Knife

- Duct Tape

- Small hatchet

- Sleeping Bag

- Water treatment system