Learn About Rockfish

Learn Alaska Rockfish

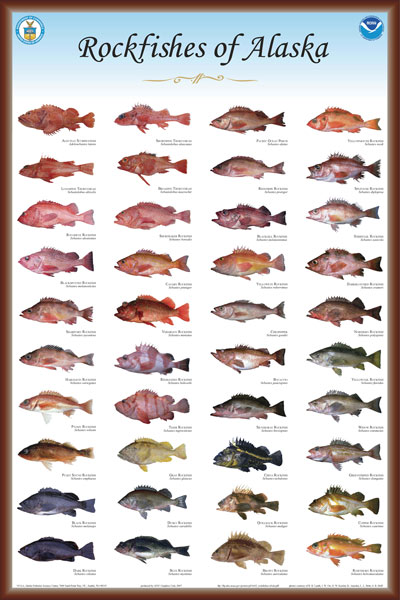

Rockfish are kind of like the redheaded stepchild of the Alaska seafood family. For one, many of the 37 species of rockfish found in Alaska are either ginger-colored or blaze orange. For two, they have a spiny top fin that sticks up like an unfortunate cowlick. And for three, well, nobody ever makes a trip to Alaska specifically to catch a rockfish. (Have you ever noticed how only one out of every 500 or so "look at me and the huge fish I caught in Alaska" photos features something other than a salmon or a halibut?)

Add to all this the fact that rockfish are extremely bony, with an effort-to-enjoyment ratio of about 60/40; they're everywhere (like dandelions) and relatively easy to catch; and the act of catching many rockfish species actually kills them (i.e., they cannot be caught and released), you've got a nuisance fish on your hands. (No wonder no one takes pictures with them!)

Still, as unappreciated and difficult as they are, rockfish are absolutely delicious, perfect for fish stews, ceviche, or fire-roasted and served whole. True, with street names like "Quillback," "Tiger," "Clown Fish" and "Yellow Eye," they sound more like a family of circus performers than a shoal of bony white fish, but who are we to judge? They're all delicious ... and waiting for you in Ketchikan!

Rockfish Reproduction

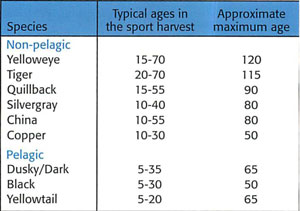

Rockfish are among the longest-living vertebrates on earth. Non-pelagic species generally live longer than pelagic species. Yelloweye rockfish, for example, reach ages over 100 years. Rougheye and shortraker rockfish occasionally exceed 150 years of age. Many of the rockfish you catch today were frolicking in kelp beds during the 1930's, and some were around when Alaska was purchased from Russian in 1867.

Most rockfishes do not start reproducing until they are at least 5-7 years old, and some may not reproduce until they're 15-20 years old. Unlike egg-laying fishes, rockfishes mate and fertilize the eggs internally. The developing embryos receive nourishment from the female. After several months, the females give birth to thousands or millions of tiny larvae. Most of the larvae are swept away by currents and eaten by other animals. The survivors settle onto the ocean floor and hide in kelp, eelgrass, or around rocks. As juvenile fish grow and mature they move to adult habitats in deeper water.

The survival of larval rockfish is believed to be closely linked to oceanographic factors such as temperature, currents, and food availability. Rockfish have evolved to live long and produce millions of offspring each year, allowing their populations to persist through long periods where conditions are unfavorable for survival of offspring.

Sustaining Rockfish Populations

Rockfish are more vulnerable to overfishing than most other fishes. They prefer rocky habitats, which fishers can easily locate using navigational charts or sonar. Once found, rockfish are relatively easy to catch. Most species grow quickly in their first few years of life, becoming fairly large before they are mature. Catching fish before they can reproduce impairs the population's ability to replace itself.

A major factor contributing to the vulnerability of rockfish is that their swim bladder (a balloon-like organ used to adjust buoyancy) is not vented. When rockfish are brought to the surface from deep water, the air in the swim bladder expands, compressing internal organs and often forcing the stomach inside out into the mouth. Fish released in this condition cannot re-submerge and will likely die. There may be other less noticeable injuries to eyes, blood vessels, and internal organs that can cause death long after the fish is released, even if it appears to swim away normally.

When you consider their ease of capture, limited movements, late maturity, low annual productivity, and low survival rate when released, it is easy to see why rockfish populations are vulnerable to overfishing. However, recreational and subsistence fisheries in Alaska are managed under some of the most restrictive bag limits on the Pacific Coast, usually with special provisions for the less productive non-pelagic species. Strict fishing regulations help maintain a healthy rockfish population in the Ketchikan area.

Pelagic and Non-Pelagic Rockfish

To the rights is a table that shows the typical maximum ages, in years, of common rockfishes in the sport harvest.

Alaska sport fishing regulations divide rockfish into two groups based on their preferred habitats.

- 1). Pelagic species congregate in large schools throughout the water column, above or around rocky shelves or pinnacles. There are five species in this group, but only the black, dusky, dark, and yellowtail rockfish are common in Alaska.

- 2). Non-pelagic species usually stay close to the bottom, often in rocky areas. They are typically solitary or in small schools, and are often mixed with other species. Some species are "cryptic" – hiding in cracks or under rocks. The most common species include yelloweye, quillback, copper, silvergray, tiger, and China rockfish. Rougheye and shortraker rockfish typically inhabit very deep bays and deep waters along the edge of the continental shelf.